Digital Audio Tape (DAT)

March 7, 2024

Digital Audio Tape (DAT or R-DAT) emerged as a digital audio recording and playback format by Sony, in 1987. Resembling a Compact Cassette in appearance, it utilises 3.81 mm / 0.15″ magnetic tape within a protective shell but boasts a compact size of 73 mm × 54 mm × 10.5 mm, approximately half the size. Unlike analogue recordings, DAT employs digital recording technology, allowing for sampling rates equal to or surpassing those of a CD (44.1, 48, or 32 kHz) at 16 bits quantisation. Notably, DAT offers exact clones of digital sources, a feature absent in other digital media like Digital Compact Cassette or non-Hi-MD MiniDisc, which employ lossy data-reduction systems.

Compact Recordable Digital Audio

DAT (Digital Audio Tape)

Similar to most videocassette formats, DAT cassettes facilitate recording and playback in one direction only, unlike analogue compact audio cassettes. However, numerous DAT recorders possess the capability to record program numbers and IDs, enabling the selection of individual tracks akin to CD players. Despite being positioned as a successor to analogue audio compact cassettes, DAT failed to gain widespread consumer adoption due to cost and concerns within the music industry regarding unauthorised high-quality copies.

Nevertheless, it found moderate success in professional markets and as a computer storage medium, eventually evolving into the Digital Data Storage format. With Sony ceasing production of new recorders, accessing archived DAT recordings may prove challenging unless copied to alternative formats or hard drives. Additionally, the emergence of sticky-shed syndrome poses a threat to audio stored exclusively in this medium, prompting concerns among engineers tasked with re-mastering archival DAT recordings.

DAT tapes were renowned for their compact dimensions, measuring approximately 73 mm in width, 54 mm in height, and 10.5 mm in thickness. This sleek and portable form factor marked a significant advancement in audio storage technology, being roughly half the size of a traditional Compact Cassette. Despite their diminutive size, DAT tapes offered ample storage capacity and high-quality audio recording capabilities.

Sony produced a ‘cleaning tape’ for the DAT machines they produced, they were however known to be a little abrassive.

Most of the major tape manufacturers produced tape for DAT during the peak period of the format.

Consumer and professional

DAT Recorder Technology

DAT technology is heavily influenced by video recorders, employing a rotating head and helical scan method for data recording. This design distinguishes DATs from analogue tapes or open-reel digital formats like ProDigi or DASH, as they cannot be physically edited in a cut-and-splice manner. The standardisation of DAT began in 1983 with the establishment of a meeting to unify digital audio recording standards across companies.

By 1985, two standards emerged: R-DAT (Rotating Digital Audio Tape) with a rotary head, and S-DAT (Stationary Digital Audio Tape) with a fixed head. While S-DAT resembled the Compact Cassette format, challenges in developing a fixed recording head for high-density recording led to the adoption of the rotating head for R-DAT, leveraging its success in VCR formats like VHS & Betamax. Although R-DAT became synonymous with “DAT,” an S-DAT media format later emerged as the Digital Compact Cassette. Sony further introduced the NT R-DAT format to replace Microcassettes and Mini-Cassettes.

The DAT standard offers four sampling modes: 32 kHz at 12 bits, and 32 kHz, 44.1 kHz, or 48 kHz at 16 bits, with some recorders supporting recording at 96 kHz and 24 bits (HHS). Early consumer-market machines lacked 44.1 kHz recording capability, preventing them from ‘cloning’ compact discs. Sampling quality directly impacts recording duration, with lower quality allowing longer recording times on the same tape. Subcodes embedded in the signal data facilitate track indexing and fast seeking. While two-channel stereo recording is supported under all sampling rates and bit depths, the R-DAT standard allows for 4-channel recording at 32 kHz.

“DAT tapes vary in length from 15 to 180 minutes, with a 120-minute tape measuring 60 meters. Longer DAT tapes pose challenges due to thinner media, with transport speeds varying based on the sampling rate, ranging from 8.15 mm/s for 48 kHz and 44.1 kHz to 4.075 mm/s for 32 kHz. It the professional world, the 120 minutes would be avoided as the thinner substrate was prone to stretching and at times, getting tangled in the machine in the worst cases.”

“The Sony DTC-1000ES DAT Recorder holds the distinction of being the world’s first commercially available Consumer DAT recorder. Introduced by Sony, the DTC-1000ES revolutionised audio recording in 1987. Its advanced features and high-fidelity recording capabilities set a new standard for audio consumers, well, at least those who got on board.”

The End of an Era

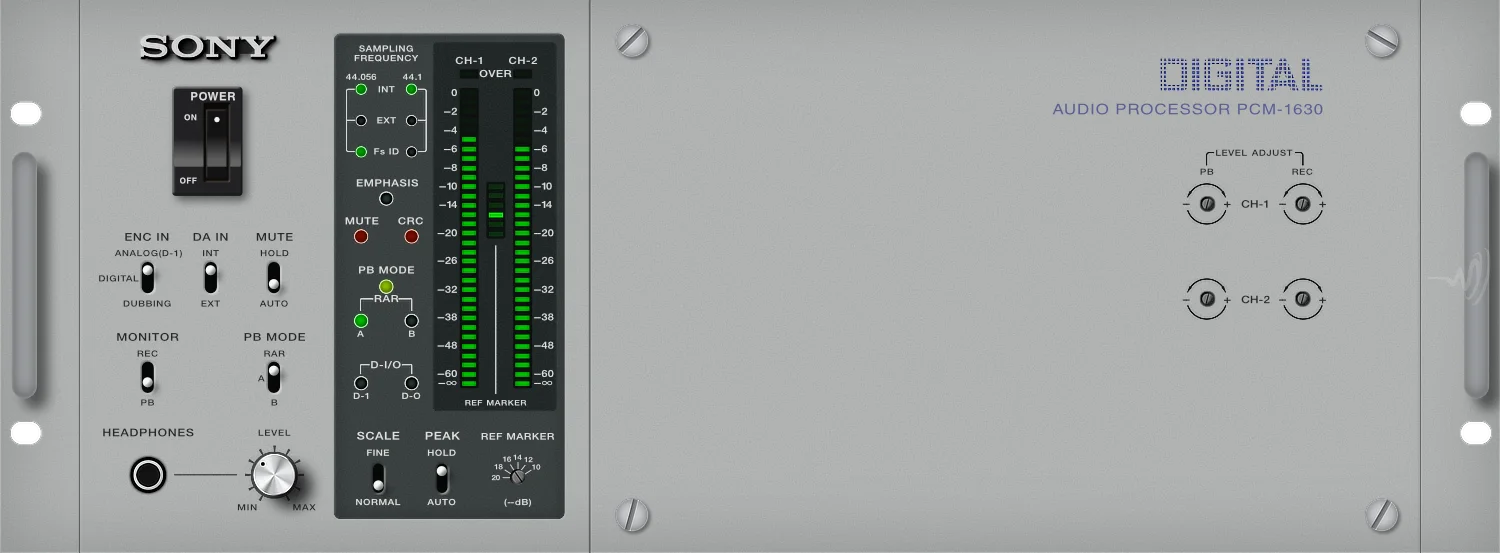

Sony PCM-1630 Processor

The Sony PCM-1630 and Sony DMR-4000 Master Recorder were groundbreaking devices used for audio mastering before the advent of the DAT format. The Sony PCM-1630 is a digital audio processor, designed to be used with a Sony BVU-800DA/800DB videocassette recorder, a DMR-2000/4000 digital master recorder or any other Sony professional VTR to create a professional PCM recording and playback system. Although there were a few predecessors, this system was the final ‘system’ prior to the release of the DAT format.

Upon the release of the aforementioned Sony DTC-1000ES, a number of studios used it to create their masters, until Sony released their first professional model, the Sony PCM-2500, which was in essence, a DTC-1000ES drive mechanism, with a second chassis containing all of the electronics. Being a professional machine it was capable of recording at the CD rate of 44.1kHz, where the consumer model could not, making it far better suited for mastering duties.

Sony PCM-2500 Professional DAT Recorder

The Sony PCM-2500 was the first commercially available professional DAT recorder designed specifically for studio mastering. Introduced by Sony, a leader in audio technology, the PCM-2500 revolutionised the audio recording industry upon its release. Offering pristine digital audio quality and advanced features tailored for professional mastering applications, the PCM-2500 became a ‘must have’ in recording studios worldwide. Its robust construction, versatile connectivity options, and precise recording capabilities set new standards for audio engineering, making it an indispensable tool for mastering engineers seeking uncompromising quality and reliability…for it’s time.

Consumer DATs Downfall

The SCMS (Scums) Chip

In the late 1980s, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) mounted a campaign against the introduction of DAT devices into the United States. Initially, the organisation threatened legal action against any manufacturer attempting to sell DAT machines in the country. Subsequently, it sought to impose restrictions on DAT recorders to prevent the unauthorised copying of LPs, CDs, and prerecorded cassettes.

One such effort, the Digital Audio Recorder Copycode Act of 1987 (introduced by Sen. Al Gore and Rep. Waxman), championed by CBS Records president Walter Yetnikoff, proposed the incorporation of a technology called CopyCode into DAT machines. This required the inclusion of a chip to detect attempts to copy material recorded with a notch filter, resulting in distorted sound for copyrighted prerecorded music, whether analogue or digital.

However, a National Bureau of Standards study revealed that the effects were clearly audible and ineffective at preventing copying, thus averting the audible pollution of prerecorded music. CBS’s opposition softened after Sony, a major DAT manufacturer, acquired CBS Records in January 1988. By June 1989, an agreement was reached, with the only concession to the RIAA being a practical recommendation from manufacturers to Congress.

This recommendation led to the enactment of legislation requiring recorders to incorporate a Serial Copy Management System (or SCMS for short, and referred to those who opposed it, the SCUMS chip) to prevent digital copying beyond a single generation. This requirement was established as part of the Audio Home Recording Act of 1992, which also imposed “royalty” taxes on DAT recorders and blank media.

One of the primary drawbacks of SCMS was its limitation on making digital copies of audio recordings. Specifically, SCMS mandated that digital copies could only be made from an original source, such as a CD or a professionally produced DAT recording. Attempting to copy a digital recording onto another DAT tape resulted in the recording being flagged as a second-generation copy, and subsequent attempts to copy from this tape were prevented. This restriction significantly hindered the flexibility and convenience of DAT recorders for consumers, who often wanted to make backup copies of their personal recordings or share recordings with friends.

Furthermore, the presence of SCMS added complexity to the user experience and led to confusion among consumers. Many users found it difficult to navigate the SCMS restrictions and were frustrated by their inability to copy certain recordings. Additionally, SCMS raised concerns about interoperability between different brands of DAT recorders, as some manufacturers implemented SCMS differently or chose not to support it at all (Some high-end Professional DAT Recorders did not have this restriction).

Overall, the implementation of SCMS had a detrimental effect on the popularity and adoption of DAT recorders in the consumer market. The restrictions imposed by SCMS limited the appeal of DAT recorders for casual users and contributed to the eventual decline of the format in favour of other digital recording technologies.

Professional

Recorders

DAT found widespread use in the professional audio recording industry during the 1990s and continues to be utilised to some extent today, primarily due to the extensive archives created during that era. While most record labels have implemented programs to transfer these tapes to computer-based databases, DAT’s lossless encoding ensured the creation of secure master tapes without introducing additional tape noise (hiss) onto the recording.

With the right setup, a DAT recording could be created without the need for analogue decoding until the final output stage. This was made possible by utilising digital multi-track recorders and mixing consoles to establish a fully digital chain, allowing the audio to remain digital from the initial AD converter after the mic preamp until it reaches a CD player.

While initially developed by Sony, the DAT format garnered widespread adoption among numerous other professional recorder manufacturers, including Studer, Panasonic, Otari, Fostex, Tascam and others. Over time, these manufacturers crafted exceptional machines that played pivotal roles in the mastering of many classic recordings. A few of these amazing machines appear below…

Otari DTR-90 DAT Recorder

The Otari DTR-90 is a well-regarded professional DAT recorder, known for its high performance and reliability. As Otari’s top model in this category, it offered advanced features and precise engineering, making it a popular choice for mastering studios and professional audio production.

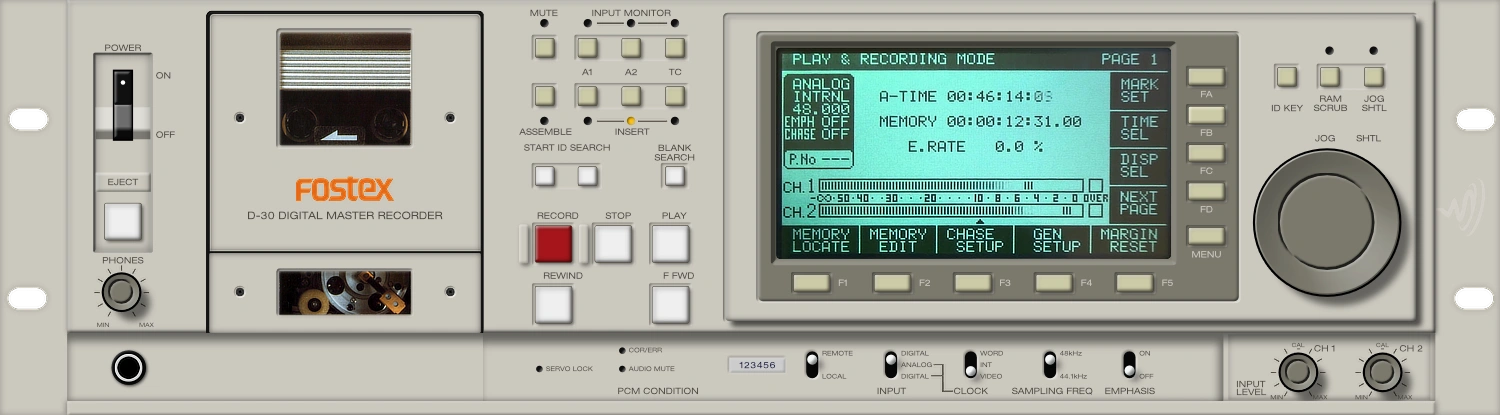

Fostex D-30 DAT Recorder

Fostex introduced timecode DAT in 1987, combining expertise in tape transport control with emerging digital technology. At the time, this innovation was regarded as a major breakthrough in the industry, and its impact is still evident in recording studios worldwide. This progression continues with the release of the Fostex D-30.

Studer D780 DAT Recorder

The Studer D780 is a professional DAT recorder known for its audio quality and durable construction. As one of Studer’s high-end models, it showcased the company’s approach to DAT technology at the time. Used in mastering studios and professional audio production, the D780 was valued for its reliability and precision, making it a common choice among audio engineers.

Sony PCM-7050 DAT Recorder

Introduced in 1996, the Sony PCM-7050 was one of Sony’s finest DAT recorders. With it’s precise electronic editing, video/audio editor interface and many postproduction and on-air facilities, it found applications in many areas of professional audio – from simple recording/playback to audio-follow-video editing, as a program source in CD mastering, for program transmission and in multi-recorder sound effects libraries.

Tascam DA-45HR DAT Recorder

The Tascam DA-45HR was the world’s first digital audio tape (DAT) recorder that supports 24-bit recording. It boasts the ability to capture high-resolution data and record it onto the standard DAT tape, thereby providing an affordable and straightforward option for professional-quality 24-bit recording. The Tascam DA-45HR was not limited to only 24-bit recording. It could also operate as a standard 16-bit DAT recorder, allowing for the reading and writing of DATs created on typical DAT machines.

The DAT format which had proved a little fragile over the years, was eventually replaced by more reliable formats such as CD Recorders, and later Magento Optical recorders. Sony concluded its production of DAT products with the release of the DAT Walkman TCD-D100 in 1995 (a consumer model), maintaining production until November 2005 when the remaining DAT machine models were slated for discontinuation the following month. With an estimated 660,000 DAT products sold since its introduction in 1987, Sony sustained the production of blank DAT tapes until 2015, announcing their cessation by year-end, thus, ending the DAT era.